Bypassing Phone Number Verification

- Odysseus

- Offensive security

- April 24, 2019

In this post I’ll show you how I bypassed the phone number verification process in a website. I’m also going to explain why this was possible and what we can do to prevent this type of vulnerability.

What is phone number verification

When you create an account in some website, sometimes they ask you to verify the phone number that you inform in the registration process. They send a SMS to the number you provided and ask you to type the code that came in that message. This way, they know that the number you informed is really yours. Doing that means that your account is now linked with an official mobile phone number, which is linked to your name. This is a form of identity verification.

Why do they ask for a mobile number verification

These verification processes allow the websites to link the accounts to real people. They do so because they want to prevent mass account creation by bots. This also helps to keep hackers from doing bad things using those accounts, because if they do, their mobile numbers are attached to their accounts, making it easier to identify them.

The wrong way to implement mobile number verification

To implement such security measure, we first have to know what are the best practices and also what are the types of attacks possible for this kind of scenario.

Today it’s not difficult to find free tools that automate various types of attacks against number verification processes. Based on that, we have to keep in mind for example how many digits the codes sent via SMS must have. Today, most online banking applications use seven or eight digit codes to login to the website and even to authorize transactions.

Using a four digit code today, for example, is not a secure way to verify a phone number, as we’ll see in this post. This is due to the fact that there are countless tools on the internet able to bruteforce ten thousand numbers (the number of four digit codes, from 0000 to 9999).

Another thing that websites have to keep in mind is the number of wrong tries when a person submits a code. What I mean is that we have to make sure the website does not allow bruteforcing the code. This can be prevented by puting some kind of limitation when a person enters a code. One way to do that is to force the user to send a new code and invalidate the previous after a small number of wrong tries.

The PoC

I was creating a new account for me on a website and when I went to the account settings area, I saw that they ask to verify my phone number. I followed the process and they sent a SMS to my phone, wihch I received in just a few seconds. The code was 2161, just four digits. When I saw that, I though “well, lets verify my number AND make a poc”. The first thing that I did was to boot up my Kali and fire up Burp Suite. Burp is a tool to perform security assessments on web applications. It’s a robust tool and even in its free version, a lot can be done.

Burp acts like a proxy, it stands between your browser and the web server. Doing that allows you to see all the requests that your browser generates and also the web server responses, all that before the requests/responses get to their destinations. You can also modify those requests/responses to trick the web server and sometimes bypass some security implementations.

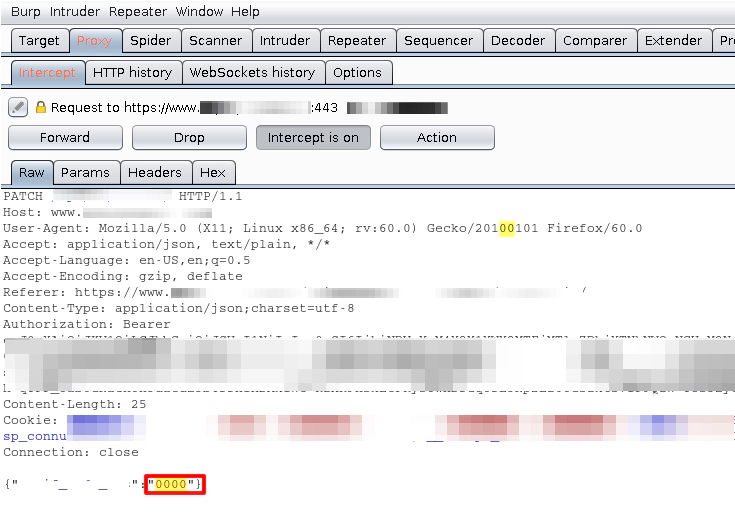

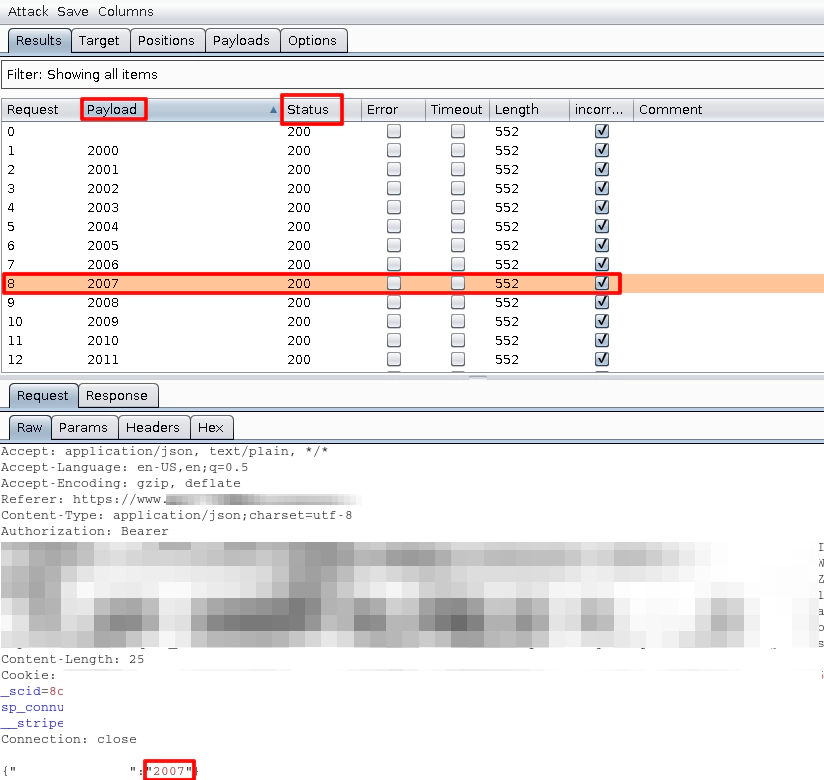

So, I used those funcions that burp provides to see how the request generated by the application after we type the code we received on the website looks like.

As we can see in the image above, the last line of the request carries the number “0000”, which was the number I typed on the website in order to force it to generate and send the request to the server. The thing is that the request never got to the web server because burp was able to capture it first.

The bruteforce process

Knowing how the request is formed, now we can make burp send thousands of requests that look just like the original one, but with the difference that the verification code will be unique for each request. The server will receive the packages and process them, looking for the verification codes and comparing them with the correct one. If one code is wrong, the web server answers that request with an error message, and if the code is correct, it validates the phone number.

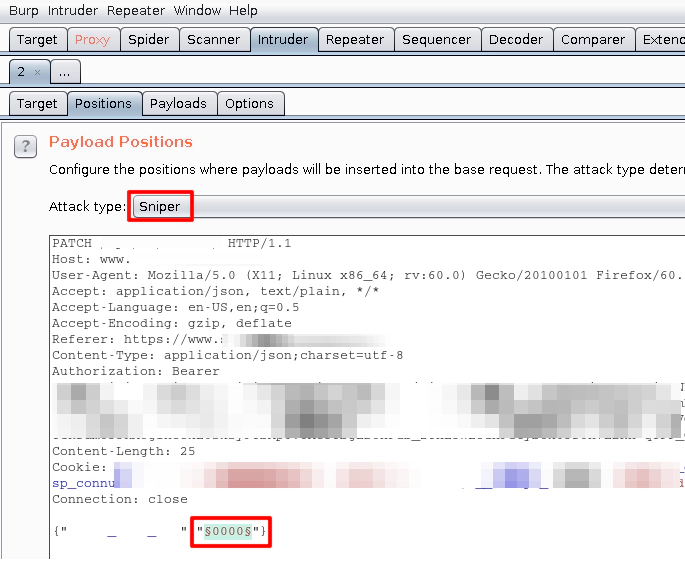

To bruteforce the code, we’ll use the burp’s Intruder tab. It allows us to mark specific parts of the request to be bruteforced. The attack method we’ll use is the Sniper, which is the simplest method.

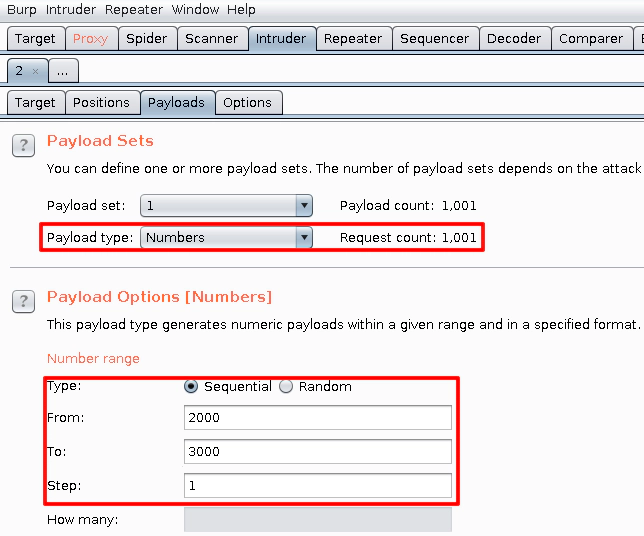

The payload tab of the intruder allows us to generate a list of numbers that will be used in the attack. Each number will be put in a single request, replacing the “0000” from the original one.

In the list, I chose to go from 2000 to 3000 because I already know the right code, which is 2161. This means that we only have to send 162 requests to get to the correct code. But in a real attack, burp would send 10000 requests, each one carrying one code from 0000 to 9999.

When we start the attack, we can see that burp starts to send the fake requests to the server, each one with its own code.

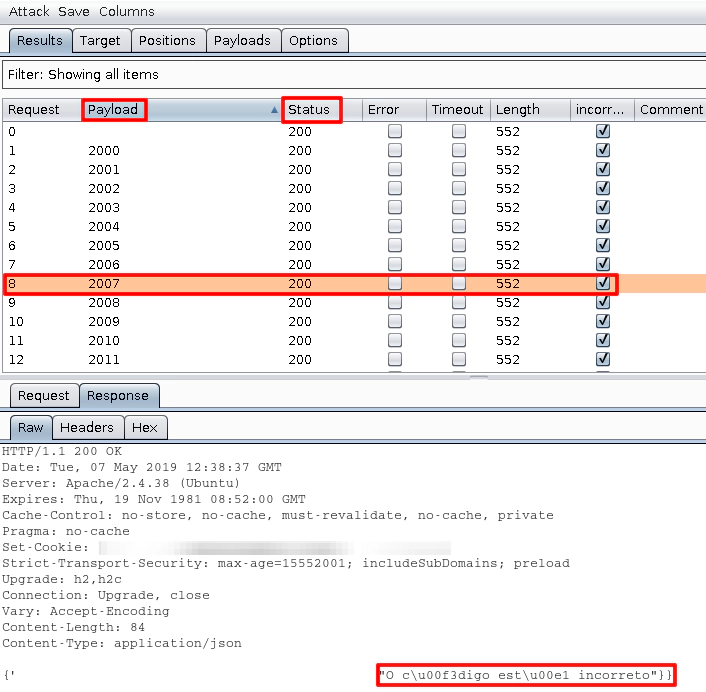

And we can also see the response from the web server, which returns an error message:

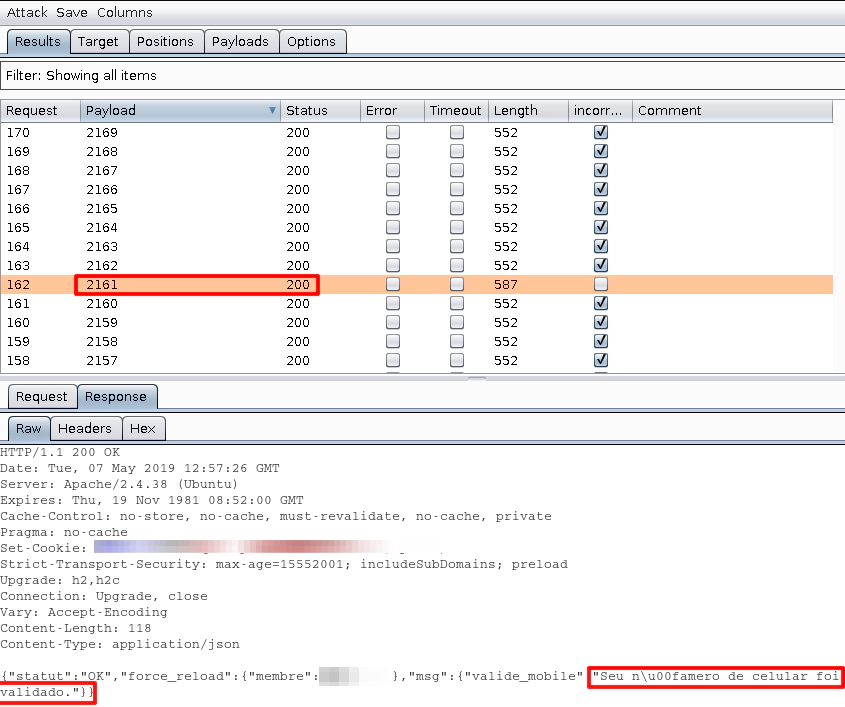

So, after a while, burp sends the correct code to the server and we can see that the response is now different, a confirmation that the code works.

“Your mobile number has been validated.” So we know that the server accepted my request with the right code. Going to the webpage I can see that my number is now green, meaning that it’s validated.

Well, that’s it. I’ll try to contact the people responsible for the website security to inform them of my findings. I hope I was able to explain the process and the concepts behind it in an easy way. See you next time!

UOLAYFIRERTRUAESBEILHIDUBGSCNOKLYFUROUSOECYACSSSTUSNOIKHOYLHOSAUEBMLOE